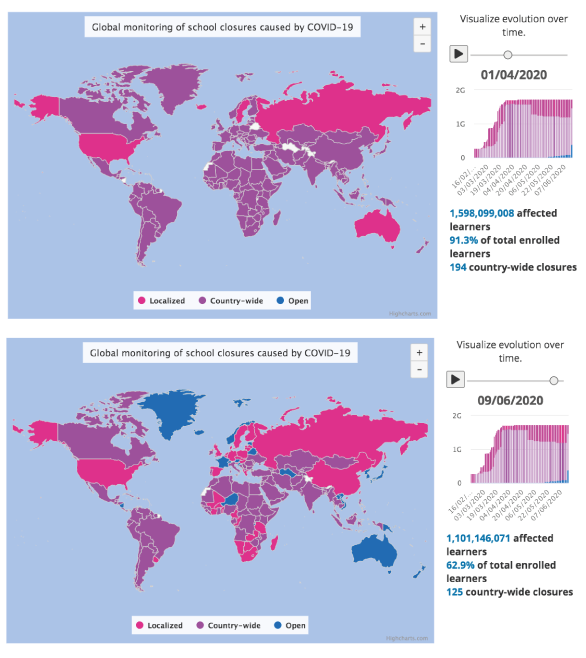

According to the United Nations, approximately 1.6 billion students – more than 91% of students around the globe – have been affected by extended school closures related to COVID-19. In many ways the biggest challenges and frontiers may lie ahead. As of this month nearly one third of those students have returned to school under radically changed circumstances.

Here we present a selection of international case studies from countries that have fully or partially reopened, with the aim of highlighting the diverse priorities and challenges that have emerged as the world goes back to school. This analysis is, of course, a snapshot of a rapidly evolving situation.

Models from the East

Having learned lessons from the SARS pandemic in 2003, Taiwan has shown the world how to minimise adverse effects on its school children. Its school closures were in reality only a prolongation by two weeks of the winter break from February 11th to February 25th, time which was used to disinfect and equip classrooms with plastic dividers, install hand sanitisers and additional handwashing facilities, distribute masks and other medical kit, and implement new procedures. The country had stockpiles of many of the required items. Thus, when students did return a fortnight late, schools were largely ready to administer temperature checks and to insist on disinfection of shoes at the gate, to schedule regular hand washing, and to enforce mask wearing. Many school classrooms employ tabletop plastic dividers around each desk and students are only allowed to remove their masks when the dividers are up. Students will make up the missed two weeks in February by the extension of the second semester from June 30th to July 14th.

In the event that a teacher or student became infected, the individual concerned was quarantined for 14 days at home. If two or more teachers or students developed a confirmed infection, the school would be closed. However, barring a suspicious sickness at a school in Kaohsiung at the time of writing, this has hardly occurred. Despite being densely populated with 24 million people, Taiwan has suffered barely 450 cases of Covid-19 so it is hardly surprising that over 70% of Taiwanese secondary school students have reported that the measures to protect against the spread of Covid-19 have not affected their learning.

Vietnam, albeit with a population almost four times as large, has suffered even less infection than Taiwan yet did close its schools for about 3 months, reopening May 11th. Schools are now following similar precautionary procedures to those in Taiwan and there may be an extension of this school year into July, shortening the break before the 2020-21 year begins by about a month. By contrast, Thailand’s rate of infection was a little higher and the country responded by delaying the beginning of its 2020-21 state school year from May to July 1st. Students have not been idle during the extension of their normal March-April holiday time since the Government put in place an educational TV channel to assist those students without access to computers and internet at home. Our partner in Bangkok, Nanmeebooks, helped its school customers with a summer offer of Maths-Whizz to cover the extended holiday break and with a view to minimising learning loss. Thailand is planning to shorten holidays later in the school year to compensate for the delayed start.

Building confidence to reopen by engaging schools and families

Away from South East Asia, another nation that has received praise for its timely and effective response to Covid-19 is New Zealand. The island nation of five million people shut down rapidly upon the onset of the pandemic, and issued comparatively clear guidance on a phased approach to re-opening. The swiftness of the measures implemented, coupled with favourable geography, caused New Zealand to remain one of the few nations without a widespread outbreak of the novel coronavirus.

In March, with only a hundred known cases of COVID-19, Prime Minister Jacinda Adern announced strict work restrictions as part of a “go hard and go early” approach to addressing the global pandemic. The initial response, during the period of community transmission, included closing the borders, preventing public gatherings, and closing non-essential businesses and schools.

Concerning school closures, the New Zealand academic calendar in many ways worked in favor of both schools and families. New Zealand operates on an academic calendar with four 10-week terms, with the first three terms separated by two-week breaks. The first academic term began in early February and by the time school closures were announced in late March, students had already completed eight weeks of the first term.

Given this fortuitous timing, school closures in New Zealand occurred a mere two weeks prior to a planned Easter holiday. As a result, New Zealand schools were able to move forward their planned school holiday period and manage their school closures with less severe disruption to instruction than schools in many other nations. This also gave educators time to adjust to their new context.

Following the Easter holiday, students engaged in distance learning until May 11th when schools officially reopened. This distance learning program involved investments in arranging internet connections and computer access for tens of thousands of families and whānau (extended families in Maori). This was complemented by the distribution of a quarter million packs of printed learning materials, and dedicated home learning TV broadcasts.

With widespread testing in place, New Zealand emerged from seven weeks of lockdown in a promising place with only 1,504 total infections and 21 deaths recorded after testing over 250,000 residents. As of this writing, New Zealand is considered to have completely eradicated the virus, recording more than three weeks without a single new infection, while more than seven million people have been infected globally.

As participants in one of the first education systems to fully re-open, school leaders in New Zealand have observed a striking trend during the first few weeks after returning to school. In spite of internationally recognised success containing the virus, one of the largest challenges faced by New Zealand schools is lingering anxiety among students and their parents.

One dimension of this challenge has been parents and caregivers who are anxious about whether appropriate safety measures are in place to create a safe learning environment. Similar sentiments have been expressed by families in other countries that also recently reopened their schools, such as Denmark and Israel.

Additionally, the ‘new normal’ may be exacerbating students’ experience of toxic stress that had been observed prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, many New Zealand schools have prioritised socio-emotional learning and mental health support strategies during the beginning of the new term. This approach will likely be relevant to countries across the world, as post-lockdown anxiety appears to be a global phenomenon.

New Zealand, like much of the world, is evaluating the path forward for building back better. A key area of New Zealand educators’ focus at present is very modern, but decidedly low-tech in nature —empowering students and their families with clear information and with the skills and mindsets to overcome adversity in a uniquely challenging time.

Designing schools for social distancing

Globally, a variety of different measures are being taken to ensure the health and safety of students and educators. Norway, Denmark, and Israel have all reopened schools with desks spaced six feet apart to maintain social distancing. Enhanced hygiene practices are being implemented, and increasingly outdoor spaces are being used for instruction based on guidance from public health authorities.

Many schools are increasing the number of entry points in order to prevent congestion which could lead to transmission. In Israel, pupils have staggered arrival times to reduce overcrowding. In both Denmark and Israel, parents are not allowed to enter school buildings in an attempt to protect against transmission. Some school systems are considering additional measures for reducing exposure, such as implementing alternate day attendance.

Progressive re-opening

Covid-19 only arrived in most countries of South America in early to mid-March but the suffering has already been considerable, especially in Mexico, Ecuador, Peru, Chile and Brazil. In Peru, the situation is already so dire that schools have been closed until December. However, one country which has limited the effects of the pandemic as successfully as any is Uruguay with case numbers of only 850. As a result, having closed its schools just as the new school year was beginning in early March, a progressive re-opening has now begun, rural and special needs schools first with schools in the more densely populated cities at the end of June to take account of the greater risk of infection in urban schools and more doubts concerning safety among parents. In some schools here, students may begin with half-days only to facilitate smaller class sizes, there will be staggered breaks, and canteen services may not restart immediately. Uruguay is well situated because its Plan Ceibal, inaugurated in 2007, makes it the leader in online learning in Latin America, and capable of supplementing classroom time effectively with distance learning at home.

Reimagining learning environments with ‘bricks and clicks’

Several countries that are reopening are placing a renewed strategic focus on ensuring that their schools can support blended learning. Across the globe schools are recognizing that having a mature capacity to deliver both online and in-person instruction creates a resilience against disruptions, whether caused by a resurgence of COVID-19 or by other unanticipated challenges.

In the United States, organisations as politically diverse as the American Federation of Teachers and the American Enterprise Institute have included recommendations for maintaining and expanding remote learning. They highlight the importance of being able to maintain continuity of learning if staggered attendance is required, as well as ensuring that schools are prepared for future shocks.

Across the pond, the Scottish Education Secretary, John Swinney has noted that he expects that blended learning will extend for at least the next academic year, as Scotland navigates re-opening based on the latest scientific advice and evidence.

The Scottish government’s rationale for directing a national approach to blended learning is particularly notable for its clarity. The Scottish ‘Excellence and Equity’ framework calls attention to the fact that school closures have an adverse impact on children’s progress and development, including ‘hidden harm’ that leads to additional cognitive, emotional, and behavioural needs over the medium and longer term. Citing evidence from the London School of Economics, and the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the framework draws particular attention to the disparate impact on working class and poor children. At the same time, the Scottish government has recognised that it must balance concerns about educational equity against the imperative to contain and suppress the virus and minimise harms to public health.

Having been advised by health authorities that social distancing in schools will continue to be required for an extended period of time, the government has required all local education authorities to develop blended learning plans in order to maximise options for instructional delivery, consistent with public health guidelines. The Scottish Government’s strategic framework thus calls for almost all children and young people to experience a blend of in-person and in-home learning, beginning in August.

Keep calm, and carry on (cautiously and with flexibility)

Across the rest of the United Kingdom, plans for reopening schools continue to evolve. The British government initially announced a gradual re-opening of schools, beginning with first and sixth grade students on June 1st, with a focus on ensuring the ‘health, welfare, and long-term future’ of the nation. Acknowledging concerns raised by scientists and public health experts, the government planned to proceed forward with a ‘cautious’ reopening plan informed by consultation with a variety of key stakeholders. At the time, the government acknowledged that not all primary schools would be prepared to re-open on the appointed timeline. This flexibility was welcomed as schools continued to work to determine how to implement safety protocols and ensure effective delivery of instruction.

One week after partially reopening its primary schools, the British government realised how challenging the enterprise would be. By June 8th, the administration reversed its position on having five million school children return to school over the summer. While 70% of primary schools did reopen in the first week of June, a variety of factors prevented a full reopening of British schools. These included caps on allowable class sizes, teacher shortages, and requirements for social distancing, among other constraints.

In spite of these early challenges British education leaders appear to remain largely united on the significance of getting reopening right. As the details continue to be worked out, the former head of Ofsted, Sir Michael Wilshaw, has framed the aim of reopening schools as ‘avoiding a lost generation of youngsters’. Mr. Kenneth Baker, former UK Secretary of State for Education, observed in a recent op-ed in the Financial Times, the pandemic could even help British schools change for the better. In his estimation, increased access to and use of technology, the replacement of high stakes summative exams with alternative forms of assessment, and digitally mediated access to tutoring can help better prepare students for the high-skilled jobs opportunities in the modern global economy.

Common lessons from the Global South

Senegal has been seen as a leader in West and Central Africa in terms of its approach to maintaining continuity of learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Supported by the UN Multi-Partner fund, Senegal developed an innovative partnership to deploy a series of distance learning solutions adapted to different contexts and conditions.

A key element of this partnership aimed at providing access to digital resources to address the learning needs of the most marginalised children and adolescents, such as those living in rural and remote areas with limited connectivity, in refugee hosting areas, and those with disabilities, through its “Learn at Home” initiative.

The widespread use of mobile phones in Senegal has made this a feasible solution to maintaining continuity of learning for some students, but the cost of internet connectivity has limited access to many others raising equity concerns. Keeping these considerations in mind, Senegal’s Ministry of National Education (MEN) complemented its online learning platform with educational television programming which is estimated to increase coverage to 75% of the population.

Like Britain, Senegal originally announced that it would be reopening its schools in the beginning of June. On June 1, however, hours before 550,000 pupils were scheduled to return to school, the government announced a delayed reopening after several teachers in the southern part of the country tested positive for COVID-19.

So Niger is thus far the only African country to have opened its schools. One of the poorest countries in the world, beset by violence from extremist factions, Niger is actively supported by UNICEF, who have been distributing protective masks for teachers and boxes of soap, and developing guidelines to share the needs and many gaps related to the back-to-school process with all education partners.

In sum: A cautious yet bold path to reopening

Early experiences from countries that have fully or partially reopened their schools suggest some important considerations for the rest of the world as other nations prepare to bring students back to class.

Education systems must strike a balance between being cautious when it comes to the health and welfare of educators and students, and bold and innovative when it comes to ensuring robust opportunities for student learning amidst a turbulent environment. As schools integrate new technologies they must ensure that considerations of equity are at the forefront. To achieve a ‘new normal’ that is sustainable, systems need to be flexible and responsive to the needs of their local communities. As seen in Britain and Senegal, best laid plans will not always work out.

Finally, efforts to reopen schools must address the fact that students, and families are emerging from a global pandemic. Deliberate efforts to reduce the anxiety associated with such an extraordinary event, may be among the most critical initial steps that can be taken to ensure that students are successful in navigating the ‘new normal’ .