Whizz Education, analysing data from its virtual tutoring platform, holds some clues as to when and where the focus and funding of interested parties should be directed to prevent the endless widening of an attainment gap in maths within classrooms across the globe. The pandemic has only served to widen that gap.

It is likely that assessment at transitional phases in children’s mathematical educations (when mathematical reasoning skills are expected to be acquired), expose long-term disparities in their understanding of earlier content.

It is time to act to ensure that gaps in knowledge and difficulties with foundational content are resolved before educational transitions make differences in ability between disadvantaged children and their peers starkly apparent.

The Ever-Widening Gap?

Data across the board reflects the persistence of an attainment gap, which measures the difference in assessed ability between students who fall short of traditional markers and their peers, and not simply the manifestation of a gap since the pandemic.

Part of Whizz Education’s mission statement since 2004, well before the COVID19 pandemic ensued, has been to address diverse learning needs in order to solve the problem of a multi-year gap in ability across classrooms.

Earlier this month, the Educational Policy Institute (EPI) released a report funded by the Nuffield Foundation which confirmed that disadvantaged students have remained an average of 1.24 GCSE grades behind their more affluent peers since 2017. In 2020, the attainment gap between students in 16-19 education was equivalent to 4.0 A-level grades and the attainment gap in primary schools widened for the first time since stabilising in 2007.

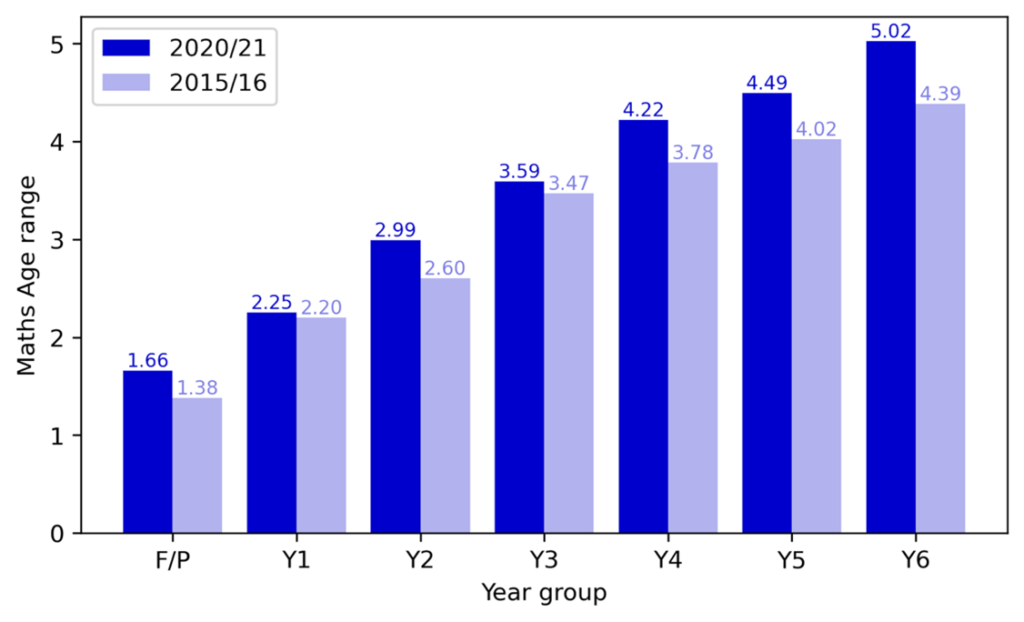

Our own data reveals that the attainment gap has simply widened, rather than materialised, over the course of the pandemic:

The previous graph also indicates that the effects of the pandemic on the attainment gap have been greatest amongst children from roughly ages eight to eleven.

The Attainment Gap at a Transitional Stage

Whizz Education has reported for a long while on the evidence of a difference in maths ability across classrooms, regions and nations using our comparative, worldwide metric of Maths Age and the real-time data we gather directly from student use of our programme, Maths-Whizz, to hold key stakeholders accountable for positive educational outcomes for all and to champion a course-corrective approach to MEL (Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning). Our latest data contains important insights which will need further investigation.

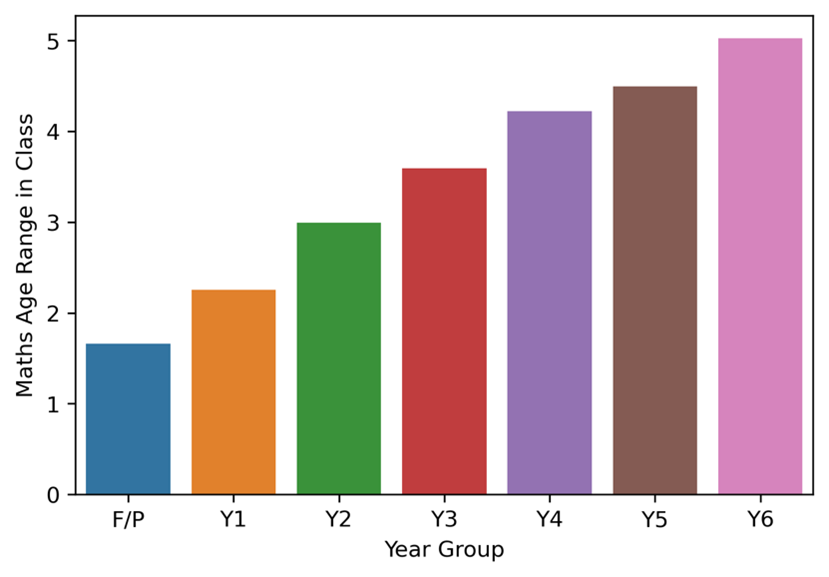

It is clear that the range of abilities in a class (the ‘attainment gap’) widens with age as children progress through primary school:

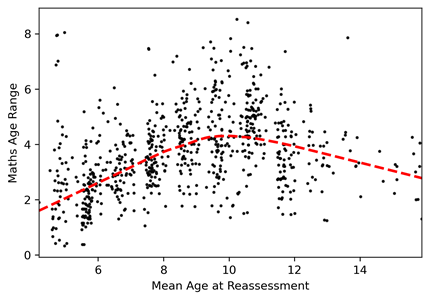

However, fitting a LOESS regression line to our scatterplot of data on the Maths Age Range of students from 764 classes who have been assessed and reassessed within the last academic year reveals the potential that the attainment gap reaches its peak width for children somewhere between ages nine to eleven:

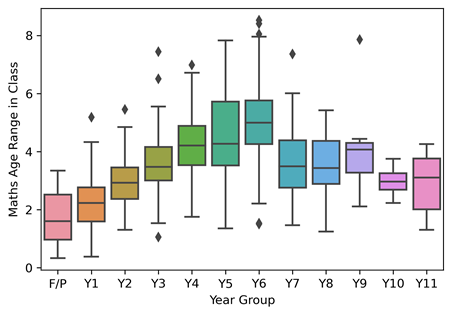

The same is reflected when the data is represented using a box-plot. Further enquiry is needed to pin-point the exact age at which the attainment gap is at its largest but, again, an age between eight and eleven (between years four and six) is strongly suggested:

It is perhaps not a surprise that the transition between lower foundational maths (years 1-4) and upper key stage two maths (late year 4-6) heralds, or exposes, a further widening of the attainment gap.

In lower foundational maths, objectives are often completed and acquired more easily as students are expected to become fluent with number systems and operations (e.g. knowing times tables and simple fractional and decimal place value) which to some degree can be achieved through memorisation.

The next stage of the curriculum really challenges and tests this fluency as students must apply mathematical reasoning to understand the relationship between procedural and conceptual maths; or, in other words, they must be able to apply core skills to solve a wider reasoning problem.

Passing earlier assessments belies unequal levels of understanding and fluency with mathematical terms and concepts amongst groups of students.

Tacking poverty to narrow the Attainment Gap

The attainment gap is also known as the ‘disadvantage gap’ – a term that better reflects the sense that students who fail to meet expected attainment levels typically experience exceptional, external barriers to their learning, such as socioeconomic hardship.

Children on free school meals are 1.6 GCSE grades behind their peers. Children in deprived areas of the UK experience a wider attainment gap than elsewhere. Black Caribbean pupils are 10.9 months behind their white counterparts by the time they sit their GCSEs. In 2020, SEND students were 3.6 GCSE grades behind their non-SEND peers. Educational inequality is fixed to the detriment of minority groups.

And the concept of ‘learning poverty’ is an important reminder that once a student falls behind it becomes difficult and eventually impossible to catch up without additional support, particularly in mathematics which is cumulative in nature and relies on a student’s mastery of prior knowledge and skills to progress to those more advanced.

The pandemic necessitated a new impetus to overcome barriers to learning and to improve the distanced delivery of educational content for all students, through the provision of internet connection, technological hardware or writing resources – the lack of which had previously prohibited students from making the expected progress.

Tackling poverty must be the first port-of-call in tackling the attainment gap, no excuses.

Our Data-driven Approach to Closing the Attainment Gap

However, the use of real-time data to reflect upon the learning journeys of students means that Maths-Whizz has a real role to play in accelerating learning for all students in order to close the attainment gap.

Our virtual tutoring tool has, at its algorithmic heart, the design to combat the attainment gap by allowing students to make, on average, 18 months of progress within the first year of use through individualised instruction.

Maths-Whizz signals to teachers when students encounter a learning blockage, fills gaps in knowledge by repeating lessons to ensure mastery and scaffolds content so that the mathematics does not surge ahead in difficulty leaving students behind.

Our data signals moments when this unique support is most essential for struggling students at transitional phases of the curriculum. For example, we might conjecture that difficulty reading, spelling and pronouncing mathematical vocabulary begins to hinder EAL students at the point when they must use language to reason and that audio support would facilitate a smoother transition. This can be embedded into pedagogical practice.

Now, our data shows the fundamental importance of working to close the attainment gap at key points in time. Decision-makers must implement a long-term policy to embed virtual tutoring tools within the classroom that are proven to accelerate learning, or else continue to protect the attainment gap in a dereliction of their duty to (an increasing number of) millions of pupils who experience (learning) poverty.