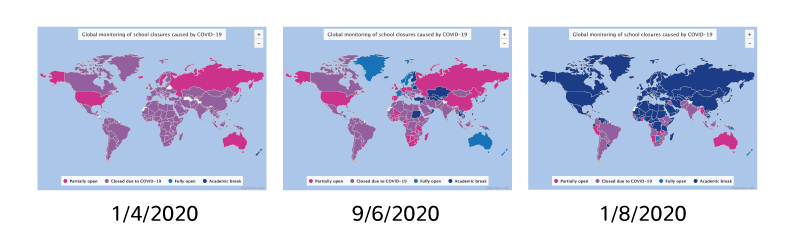

The narrative is by now familiar. Sweden’s primary and secondary facilities remained open, but every other country across the globe experienced the localised or national closure of schools due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. 1.6 billion learners were removed from school buildings by early April. Half a year later, 1.1 billion students have yet to return. As schools across Europe reopen, we take a look at what international examples of reopening teach us about the way forward.

Since June, when we shared our analysis of the ways in which various countries were choosing to reopen their schools, fourteen countries have ended their country-wide closure of schools and 2% of learners have returned to educational facilities, representing some 35 million individuals. However, ‘reopening’, notionally or in action, should not be sold as a success story in and of itself.

Not a ‘return to normal’

The prefix ‘re-’ is used to express backwards motion, the restoration of a previous state of things, or the repetition of an action. ‘Reopening’ then connotes a return to something that has been done before, but this is a misnomer.

Every attempt at reopening schools confirms one thing: returning to school is unlikely to be a ‘return to normal’. School reopenings are beset with new rules and regulations and represent a vulnerable normal at best.

Here we bring together some of the many measures schools might be expected to implement:

- One-way routes of entry and exit

- Desks spaced 6 ft apart

- Alternate-day attendance, class-by-class returns, staggered break-times

- Wearing and instalment of PPE (including masks, screens, more regular hand-washing)

- Regular temperature-taking

- Cancelled canteen-services and clubs out of school hours

- Teachers standing behind desk barricades

- Distanced, timed collection/pick-up routines

- Reconsidered transport

- Bubbled classrooms with individual teachers

- Psychosocial support activities and catch-up classes

Reopenings followed by ‘re-closures’

The following cases from the last month demonstrate that the virus, though posing a minimal risk to the health of children, can undermine attempts to return to school once they get started.

Although the virus was under control, Japan, China, Australia, South Korea, and Hong Kong are all experiencing new peaks in infection, which are forcing localised school closures. For example, schools in Beijing closed for a second time on June 16, after reopening on April 27, and Hong Kong ended the school year early on July 10.

After closing schools in late January and reopening them starting May 11, schools in Vietnam have now been closed until further notice as, despite months without a single death or confirmed case of local transmission, the country faces a new outbreak as of July 29.

In the US, schools in Los Angeles and San Diego have been closed due to skyrocketing infection rates. The State of Florida has been sued by their largest teachers union for the plan to reopen schools as 10 000 new cases of coronavirus are recorded day-after-day.

Schools have remained open in Sweden since the advent of coronavirus, but the country has experienced a death rate higher than half of Europe, unlike its Scandinavian neighbours.

Beginning a slow reopening in early May, Israeli schools too have had to close down again as of July 13. 1, 335 students and 691 staff were infected due to a hastened reopening and hot weather, which led the government to drop the requirement to wear masks.

In South Africa, schools closed in early March, reopened in early June, and 968 schools were reclosed a month later because of outbreaks in which more than 1, 260 students and 2, 400 teachers tested positive for COVID-19. Reopening schools for high school students at pace is likely to be the cause as outbreaks in French schools and Missouri summer camps are also connected to children aged 10 and above. Similarly, isolated outbreaks in the Al-Taqwa school in Victoria, Australia, with children from preparatory grades to Year 12 suggests that young children may transmit the virus less often than teenagers, perhaps implying that physical reopenings should be prioritised by age group.

Patterns to inform progress

Although the role of children in transmitting the virus remains unclear, patterns are emerging. Where infection rates are high, returns are rushed, reopening coincides with the opening of the economy, safety measures are inadequately followed, impractical, or too expensive, or older school children are involved, intermittent closures become more likely.

Successful school reopenings in New Zealand, Uruguay, Germany, and Denmark are a result of low levels of national coronavirus cases, tentative, staggered, and socially distanced returns to maximise available space, appropriate government funding, and bipartite policies combining home learning with fewer days in the classroom, as well as a degree of technological preparedness, teacher training, parent involvement, and a focus upon lessening circulating anxieties.

Traditional schooling then must be transformed if education is to be protected from frequent and periodic disruption in a COVID-context.