Teacher training needs to evolve, in both content and form. COVID-19 has confirmed as much.

There are twin pressures gesturing towards a marriage of technology and teacher training:

- COVID-induced school closures in the developing world legitimise an argument for focusing on teacher Continuous Professional Development (CPD) rather than student learning.

- Blended learning is set to become the norm and teachers require upskilling on how to deliver it effectively.

During an education crisis, teacher training can help to both ‘Build Back Better’ by improving pre-existing educational norms, and to develop structural resilience that withstands future COVID-type crises. In this shared emergency, a global, online CPD platform for teachers would deliver both: enhancing subject knowledge and pedagogical competence, while concurrently preparing teachers to support learning from distance.

1. Train teachers during an educational crisis

It sounds counterintuitive but if you want to mitigate the learning loss accumulated during a pandemic, don’t focus solely on student learning. This resonates the most in low-resource settings. Where classroom access is hopelessly curtailed and there is a paucity of household technology, relatively few learning gains will be achieved. Despite the best efforts of humanitarian actors, radio education and print materials (the go-to resource combination) are a flawed means of delivery and typically generate a low learning yield.

It is better, surely, to focus the energies of those same actors upon teacher professional development. This reflection is not new; it was shared in light of Ebola school closures in West Africa. The lessons from COVID-19 are still to be assembled, but the same logic applies here. Teachers are typically more connected to online than students. It is therefore appropriate to (remotely) develop their capacity during a period of school closure, and for the resulting knowledge and skills to be deployed at the point of reopening to address student learning loss.

This focus requires taking a punt on a medium-term outcome while appearing to drop the ball on learning in the present. But hasn’t this always been a focus of the development sphere which, after all, seeks sustainable solutions rather than sticking plasters?

2. Training teachers means Building Back Better

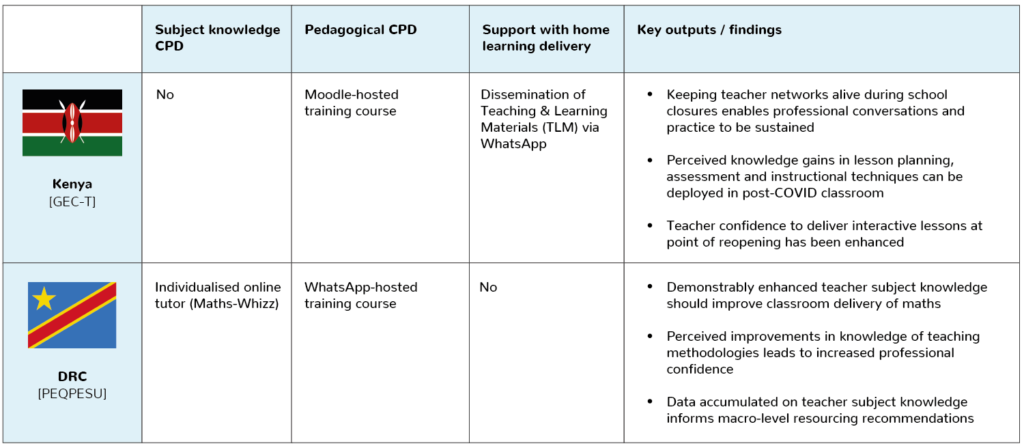

As a technology-enabled education company, Whizz’s responses to COVID-19 in Kenya and DRC have been nudged in this direction. While schools there are closed, student learning via our virtual tutoring platform is marginal. But through a focus on teacher training, we have maintained reach and influenced longer-term learning outcomes.

Much attention is directed towards COVID-inflicted learning loss, appropriately so. Our own research points to a 2.6-month learning loss over the summer, and we are currently examining losses brought about by extended closures. But quantification of learning, as a sole measure of COVID impacts, may be a red herring: teacher training during a humanitarian response has more than one aim. Building Back Better is laudable, and addresses immediate needs, as the table above shows. Teacher training can also ensure that countries are better prepared to deal with future unanticipated shocks. This idea – of building systemic resilience – is an equally important feature of the long-term recovery phase – but is less easily calculated.

3. Teacher training also builds systemic resilience

For schools in higher-resource settings, a focus on learners during COVID-19 was at least partially maintained. The availability of technology (notwithstanding socioeconomic dependencies) enabled learning to happen from home, and teachers were fully occupied in its delivery. In recent months, the question of how to sensibly organise school reopenings has dominated educational discourse. Student wellbeing and infection control now command attention on campus. Teacher training has not been a prominent area of discussion. Although some level of statutory CPD has been sustained in the UK, teacher training as a vehicle for building institutional resilience has been conspicuously absent.

Addressing subject knowledge gaps or pedagogical shortcomings is not as big a priority in these settings as it is in Kenya or DRC. That doesn’t render teacher training moot, however. As swathes of students are sent home to isolate, government guidance on remote learning has been fulsome. But the support offered to teachers to fulfil these many criteria is incommensurate. There are links to online resources, and to funding opportunities, and to ways of sourcing hardware. There are videos of teachers talking about blended learning, or the flipped classroom approach. Yet the list of urls does not practice what it preaches. Copious signposting does not, by itself, improve coordination or entrench behaviour change. It is the rare context that offers structured efforts to develop teacher competency around remote learning delivery.

It is acknowledged that the format of teacher CPD is changing: face-to-face twilight sessions may soon be a thing of the past. If blended learning is to lead to systemic resilience, it needs to be the subject of statutory CPD as well. While funding is being loudly earmarked for catchup tutoring at scale, the same is not true for teacher reskilling. Teachers are not currently equipped with the skills and knowledge to effectively deliver remote – or blended – learning. When the second phase of lockdowns come, a scattergun approach to remote delivery will feasibly reoccur (with the same imperfect outcomes) – unless deficiencies are addressed:

- Access to a chaotic multiplicity of platforms (of varying levels of quality), but little coordination among colleagues about which to deploy, let alone knowledge of how to do so effectively.

- Dramatically varied approaches between schools: some broadcasting regular live lessons, others (especially in disadvantaged schools) lacking confidence in how to deliver content online.

- Inconsistent procedures around monitoring and assessment: not all teachers providing individual feedback (e.g. via platforms like Google Classroom).

Knowledge of how to operate an online platform is only a first step. Doing so dynamically and inclusively – and in a coordinated way that enables individual progress, assessment, streamlined curriculum coverage and peer planning requires hands-on training and experience. Embedding these competencies within the teaching workforce will, in turn, embed resilience that prepares the system to cope with future shocks.

4. The medium is the message – time for a teacher ‘Academy’

We are in a shared education emergency. The humanitarian sphere can benchmark and inform how we respond globally. Now more than ever then – with COVID simultaneously driving CPD online – it is time to rethink teacher training.

The development of a modularised Teacher Academy platform could meet more than one global need: enhancing subject knowledge and pedagogy in contexts where this is a priority, and preparing teachers everywhere to meet the blended learning future with confidence.

Technology is expedient for delivering at scale, and the same algorithms that enable individualised virtual learning for students can be harnessed to create bespoke teacher development pathways. The medium of teacher training is crucial. In the same way that training on pedagogy must exemplify best teaching practices, so a platform which prepares teachers to deliver blended learning effectively must embrace a blended delivery model. There are challenges in both design and logistics regarding, for instance, the scaling of non-technological elements such as reflection, feedback and coaching. But these challenges are not intractable, and they must be tackled to address the inadequacies of traditional teacher training.

Blended learning – not just for students but teachers too – has arrived. The ball is in our court as educators and innovators. Setting sticking plasters to one side, the EdTech sector should grasp it with both hands.